Preseason No. 7 Gonzaga will face No. 21 USC as part of Dec. 2 doubleheader that also features Washington-Colorado State in Las Vegas

LAS VEGAS (September 26, 2023) – A west coast showdown between preseason top-25 programs Gonzaga and USC headlines the Legends of Basketball Las Vegas Invitational, a college basketball doubleheader set for Dec. 2 at MGM Grand Garden Arena. Washington and Colorado State will open the Saturday night doubleheader at 7 p.m. ET on CBS Sports Network and will be followed by the Bulldogs and Trojans at 10 p.m. ET on ESPN.

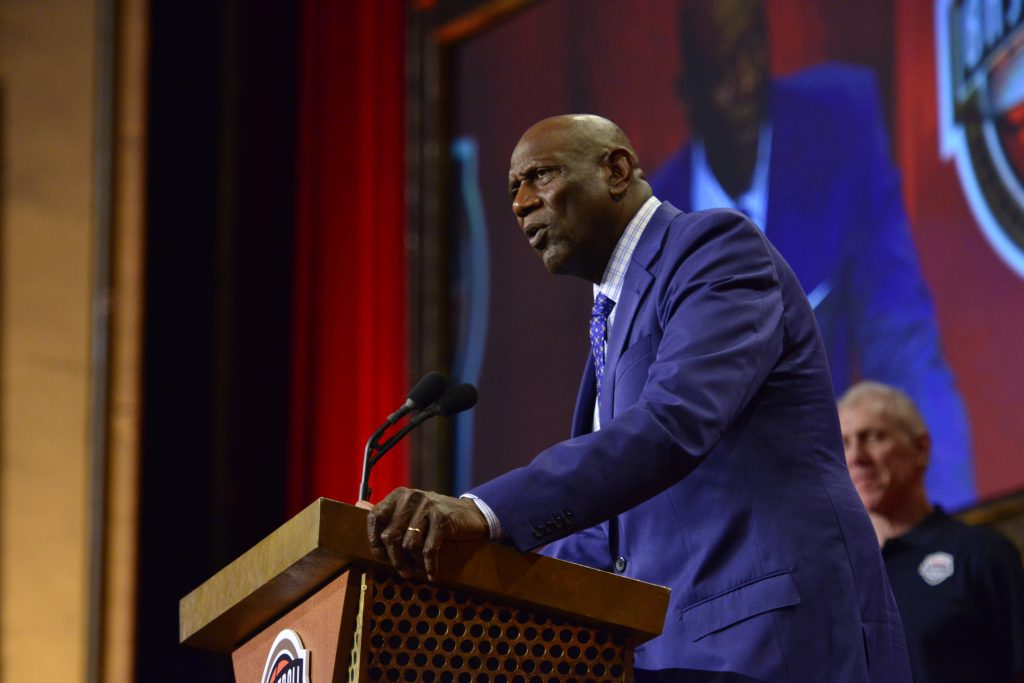

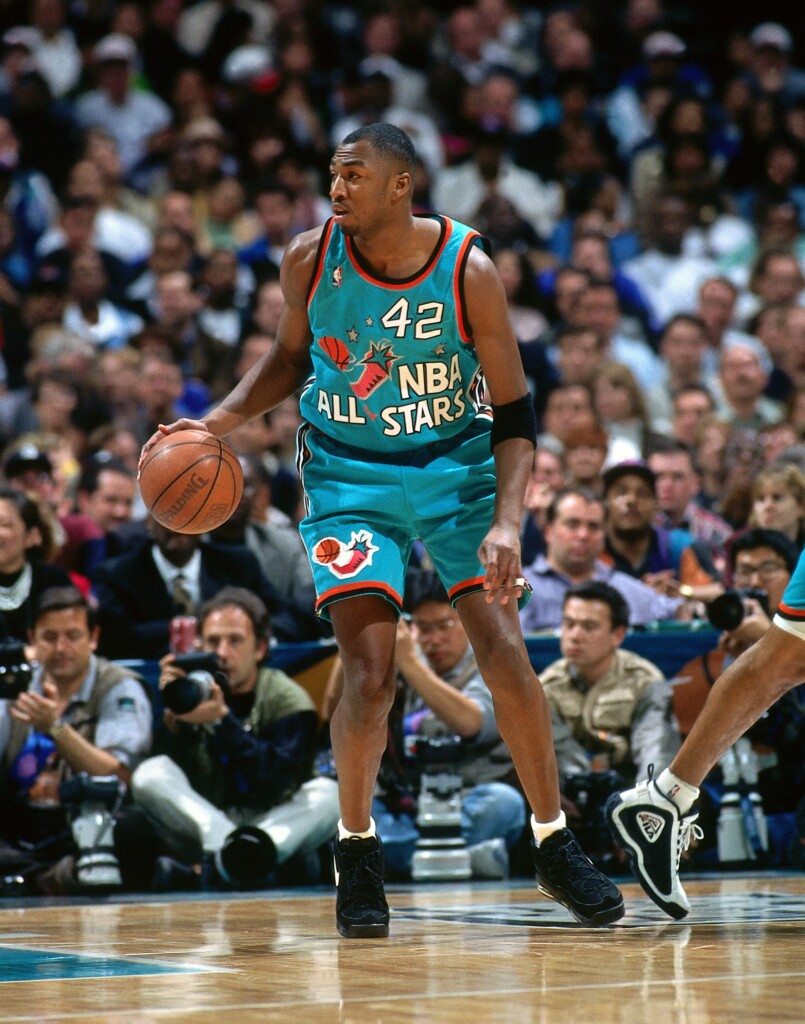

The National Basketball Retired Players Association (NBRPA) is the title sponsor of the event. Founded in 1992, The NBRPA serves former professional basketball players in their transition into life after basketball and is the only alumni association of its kind supported directly by the NBA and National Basketball Players Association. Intersport, a Chicago-based sports marketing and events agency, is the operator of the Legends of Basketball Las Vegas Invitational.

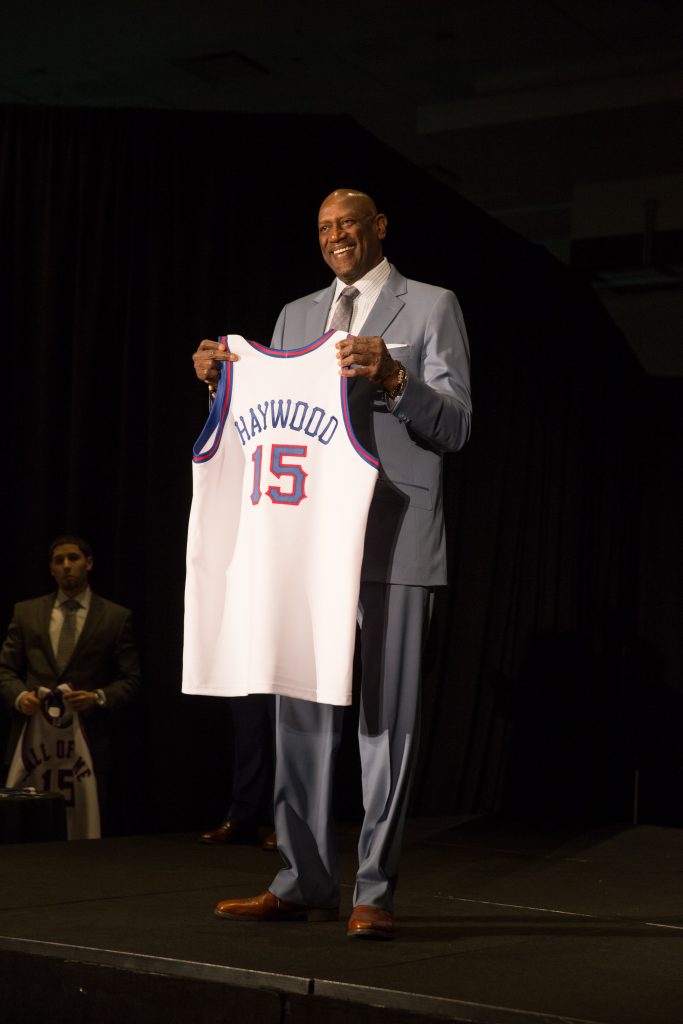

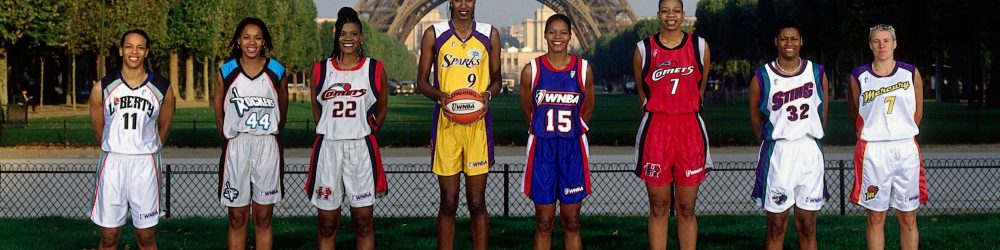

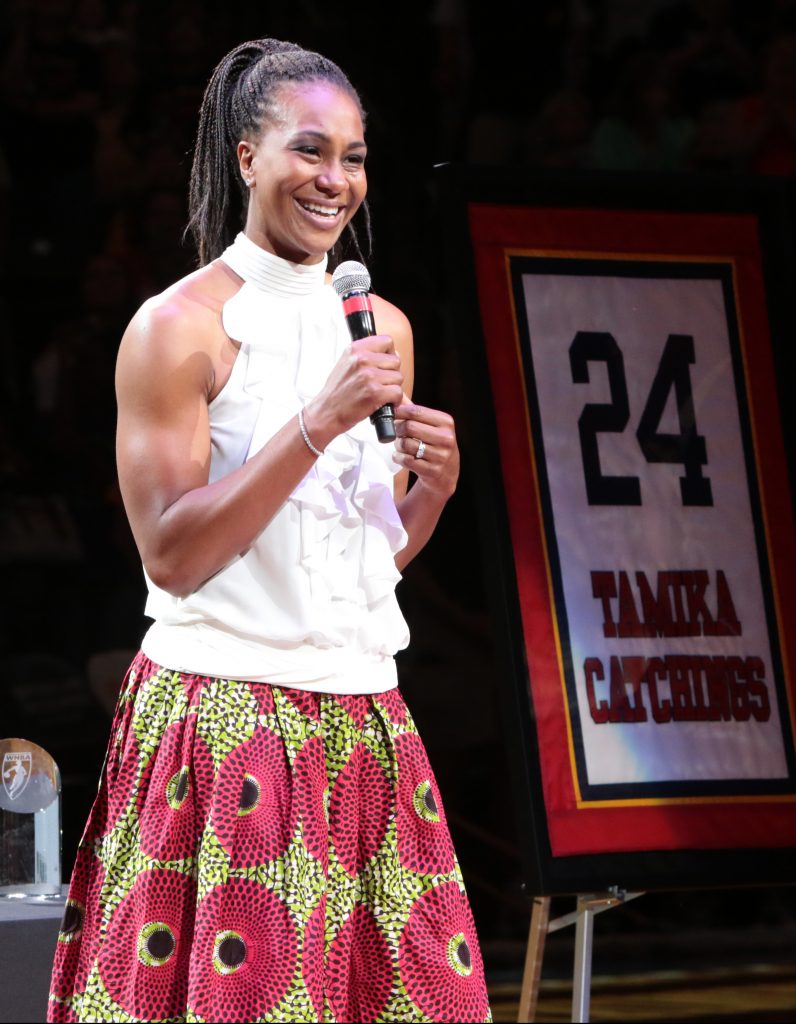

Tickets for the event will go on sale on October 13 at www.axs.com, but fans interested in attending the doubleheader can register to receive event information and gain access to early tickets through a one-day presale on October 12 by signing up at www.legendsofbasketball.com/vegas. Through the link, fans can also purchase VIP hospitality tickets to pregame and postgame events through the NBRPA for the opportunity to meet former NBA and WNBA stars.

“The NBRPA is thrilled to build on and expand our partnership with Intersport to present the Legends of Basketball Las Vegas Invitational,” said Scott Rochelle, President & CEO NBRPA. “The combination of deep NBRPA ties to the participating college basketball programs, a tremendous location in Las Vegas and a world-class venue in the MGM Grand Garden Arena, promises to make this event a must-watch for all college hoops fans. We look forward to showcasing the action and fanfare that these four renowned basketball programs are sure to bring.”

“Las Vegas is known for major, must-see events and this doubleheader fits that bill,” said Mark Starsiak, vice president of basketball at Intersport. “With four dynamic programs on the court and an engaged partner in the NBRPA, the Legends of Basketball Las Vegas Invitational will offer an incredible experience for fans. Both Gonzaga and USC are among the favorites to win their respective leagues and have extremely talented rosters that position them for dangerous runs through the NCAA Tournament, while Colorado State and Washington each have the ingredients to push for postseason berths as well.”

This will be the fourth all-time meeting between USC and Gonzaga with the Trojans owning a 2-1 mark in the series. The Bulldogs won the most recent meeting, an Elite Eight showdown in the 2021 NCAA Tournament. Washington and Colorado State have also played three times previously with the Rams having won twice, including the most recent meeting between the programs in 2012.

Both Gonzaga and USC are consensus preseason top-25 programs and should once again contend for not only their respective conference championships, but deep NCAA Tournament runs this coming season. For the preseason No. 7 Bulldogs, three impact transfers – Ryan Nembhard (Creighton), Steele Venters (Eastern Washington) and Graham Ike (Wyoming) – step in the fill the void left by departing starters Drew Timme, Julian Strawther and Rasir Bolton. Anton Watson and Nolan Hickman return as likely starters for head coach Mark Few, who is set to begin his 25th season as the Bulldogs head coach. In the last 24 years, Gonzaga has made the NCAA Tournament every season, advanced to two national championship games and made 10 Sweet 16 appearances, winning more than 83 percent (689-135) of its games since Few took over.

Preseason No. 21 USC may boast the most dynamic backcourt in the country next season as the Trojans return all-conference guard Boogie Ellis and welcome the nation’s No. 1 recruit in the Class of 2023, Isaiah Collier. Returning starters Kobe Johnson and Joshua Morgan, along with graduate transfer DJ Rodman, will give the Trojans a deep, experienced core. Andy Enfield is entering his 11th season with the program and looks to guide the Trojans to the NCAA Tournament for the fourth straight season, which would mark the longest streak in program history. Enfield’s USC teams have won 20 or more games in seven of the last eight seasons.

Sixth-year Colorado State head coach Niko Medved has established the Rams as a consistent presence in the Mountain West Conference. CSU has won double-digit conference games in three of the past four seasons. The Rams return three starters from last season’s team including four-time All-Mountain West guard and 2022 Bob Cousy Award Finalist Isaiah Stevens. Stevens led the team in scoring (17.9 ppg) and assists (6.7 apg) in 2022-23. Patrick Cartier and Jalen Lake also return from starting for CSU last year, while they add a trio of Centennial State transfers in Nique Clifford, Javonte Johnson and Joel Scott.

Washington, under seventh-year coach Mike Hopkins, returns two All-Pac-12 starters from last season – Keion Brooks Jr. and Braxton Meah – and welcomes a bevy of high caliber transfers led by Kentucky transfer Sahvir Wheeler and Rutgers transfer Paul Mulcahy. Brooks is the Pac-12's leading returning scorer after averaging 17.7 points and 6.7 rebounds per game and reunites with his former Kentucky teammate Wheeler. Wheeler was a Bob Cousy award finalist as a junior in 2022 before enduring an injury plagued season last year. Mulcahy finished his Rutgers career fourth on the program’s all-time assists list. Meah started 31 games last year, averaging 8.8 points and 7.2 rebounds per game.

The Legends of Basketball Las Vegas Invitational is one of many events that is part of Intersport’s early season college basketball calendar, which has seen considerable growth in the last five years. After initially launching a four-team event in Fort Myers in 2018, the Chicago-based agency has announced plans to host at least seven different events throughout the course of the 2023-24 season, beginning with the Radford-Marshall neutral site game at The Greenbrier in West Virginia (Nov. 10) before hosting 25 games during a nine-day stretch from Nov. 17-25. First, the inaugural Arizona Tip-Off will be held Nov. 17-19, followed by the Fort Myers Tip-Off from Nov. 20-22 and the Elevance Health Women’s Fort Myers Tip-Off from Nov. 23-25. In December, Intersport will manage the Legends of Basketball Las Vegas Invitational on Dec. 2 and the CBS Sports Classic in Atlanta on Dec. 16 before finally hosting the Ohio State-West Virginia neutral site contest in Cleveland on Dec. 30. Additional event announcements will be forthcoming in the coming weeks.

About Intersport

Since 1985, Intersport has been an award-winning innovator and leader in the creation of sports, lifestyle, culinary and entertainment-based marketing platforms. With expertise in Sponsorship Consulting, Experiential Marketing, Hospitality, Customer Engagement, Content Marketing, Productions and Sports Properties, this Chicago-based Marketing & Media Solutions Company helps their clients to create ideas, content and experiences that attract and engage passionate audiences. To learn more about Intersport, visit www.intersport.global, like us on Facebook or follow us on Twitter and Instagram.

About the National Basketball Retired Players Association

The National Basketball Retired Players Association (NBRPA) is comprised of former professional basketball players from the NBA, ABA, and WNBA. It is a 501(c) 3 organization with a mission to develop, implement and advocate a wide array of programs to benefit its members, supporters and the community. The NBRPA was founded in 1992 by basketball legends Dave DeBusschere, Dave Bing, Archie Clark, Dave Cowens and Oscar Robertson. The NBRPA works in direct partnerships with the NBA and the National Basketball Players Association. Legends Care is the charitable initiative of the NBRPA that positively impacts youth and communities through basketball. Scott Rochelle is President and CEO, and the NBRPA Board of Directors includes Chairman of the Board Charles “Choo” Smith, Vice Chairman Shawn Marion, Treasurer Sam Perkins, Secretary Grant Hill, Nancy Lieberman, CJ Kupec, Mike Bantom, Caron Butler, Jerome Williams, Clarence “Chucky” Brown and Dave Bing. Learn more at legendsofbasketball.com.

To follow along with the NBRPA, find them on social media at @NBAalumni on Twitter, Instagram, YouTube and Twitch. To follow along with the NBRPA, find them on social media at @NBAalumni on Twitter, Instagram, YouTube and Twitch.

MGM Grand Garden Arena

The MGM Grand Garden Arena is home to concerts, championship boxing and premier sporting and special events. The Arena offers comfortable seating for as many as 16,800 with excellent sightlines and state-of-the-art acoustics, lighting and sound. Prominent events to date have included world championship fights between Evander Holyfield and Mike Tyson as well as Floyd Mayweather vs. Canelo Alvarez as well as Floyd Mayweather vs. Manny Pacquiao; and concerts by The Rolling Stones, Madonna, Elton John, Bruce Springsteen, Paul McCartney, Bette Midler, George Strait, Justin Timberlake, Beyonce, U2, Lady Gaga, Bruno Mars, Coldplay, Alicia Keys, Jimmy Buffett and the Barbra Streisand Millennium Concert. The MGM Grand Garden Arena also has been home to annual events including the Academy of Country Music Awards, the Billboard Music Awards, the Latin GRAMMY Awards, iHeartRadio Music Festival, Pac-12 Men’s Basketball Championship and Frozen Fury NHL pre-season games hosted by the Los Angeles Kings.

Media Contact:

Dan Mihalik, Intersport, dmihalik@intersport.global

Julio Manteiga, NBRPA, jmanteiga@legendsofbasketball.com, (516) 749-9894