WNBA Legends Inspire Girls Inc. Teenagers Across the Country

Chicago (August 11, 2020) – The National Basketball Retired Players Association (NBRPA) is proud to announce Legends Girl Chat, a new, virtual Legends Care program consisting of one-hour video conversations between high school girls and WNBA Legends.

“The Legends Care initiative is such a vital part of the NBRPA that we were not going to allow the COVID-19 pandemic to halt our programming completely,” said NBRPA President and CEO Scott Rochelle. “The NBRPA team expertly pivoted by creating this virtual program that safely brings WNBA Legends and their inspiration and wisdom right into the homes of girls all across the country.”

Partnering with the NBRPA on Legends Girl Chat is Girls Inc. Girls Inc. provides comprehensive, research-based programs and activities for girls at sites across the United States. The mission of Girls Inc. is to inspire all girls to be strong, smart, and bold through direct service and advocacy.

"We are thrilled to partner with the NBRPA and WNBA Legends to bring the Legends Girl Chat initiative to Girls Inc. girls. Through this unique opportunity, girls are connecting with remarkable female role models and building on the experiences they are getting at Girls Inc., including learning about the importance of teamwork, using the skills they develop through sports participation to become leaders in their communities, and speaking out against injustice," said Dr. Stephanie J. Hull, Girls Inc. President & CEO.

Through this Legends Care partnership, all 78 affiliates of Girls Inc. are able to schedule a Legends Girl Chat to incorporate into their summer or afterschool programming.

“We are honored to be working with Girls Inc. and their affiliates as the Legends Girl Chat community partner,” said NBRPA Sr. Director of Social Impact and Events Bridget Gannon. “An organization with such a legacy of empowering girls was a natural fit for a Legends Care program that connects strong, smart and bold WNBA Legends to girls who they can inspire and motivate during these uncertain times and beyond.”

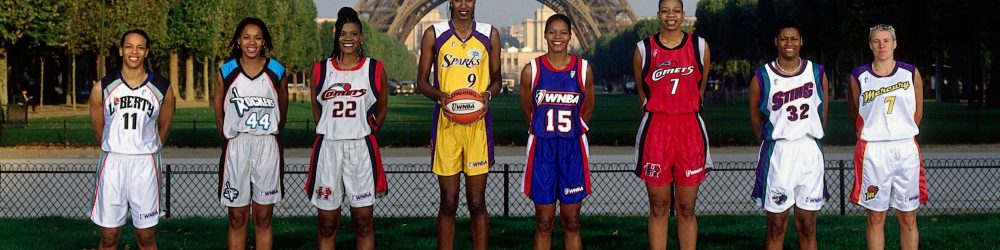

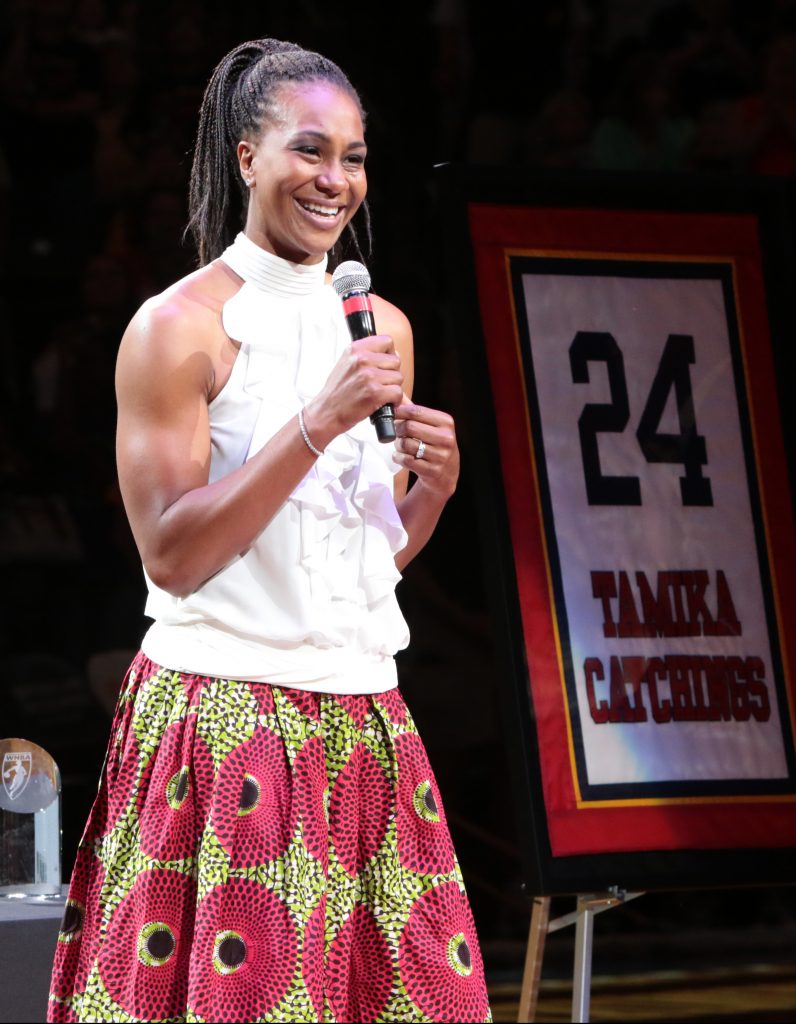

WNBA Legends who have already participated in Legends Girl Chat include WNBA Champions and All-Stars, Hall of Famers, Olympic Gold Medalists and NCAA Champions.

Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame Inductee and NBRPA Director Sheryl Swoopes adds, “For so many of us W Legends, we see ourselves in these girls and we jump at the opportunity to speak with them and impact their lives in a positive way whether the conversation is about basketball or life in general.”

A Legends Girl Chat promotional video can be found here.

###

Media Contacts:

Julio Manteiga, jmanteiga@legendsofbasketball.com, (312) 913-9400

Veronica Vela, vvela@girlsinc.org, (914) 830-1179

About the National Basketball Retired Players Association:

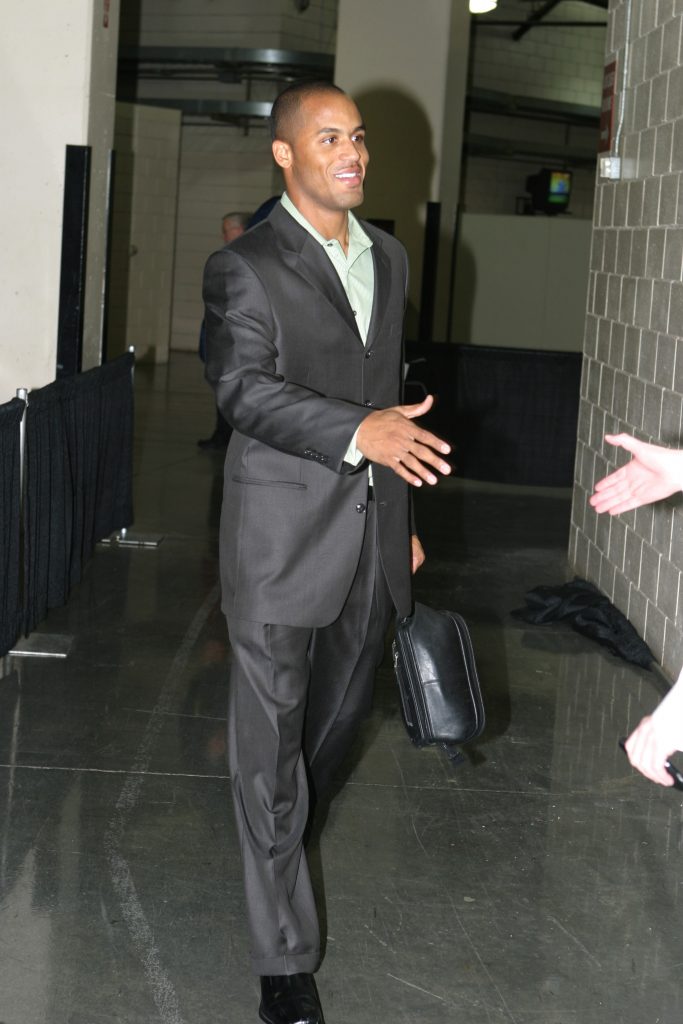

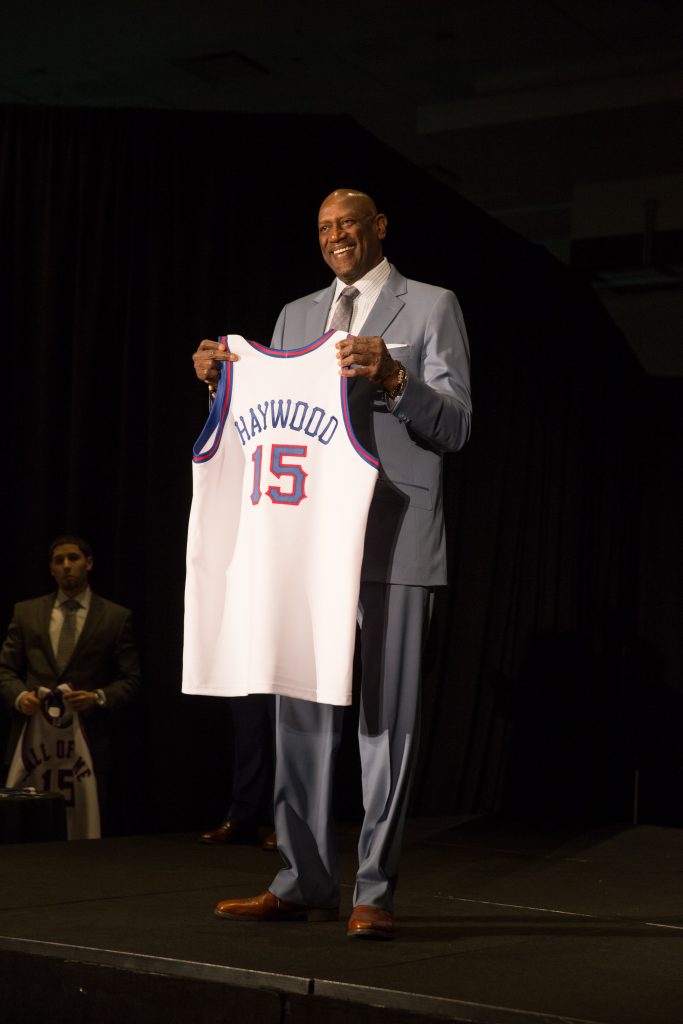

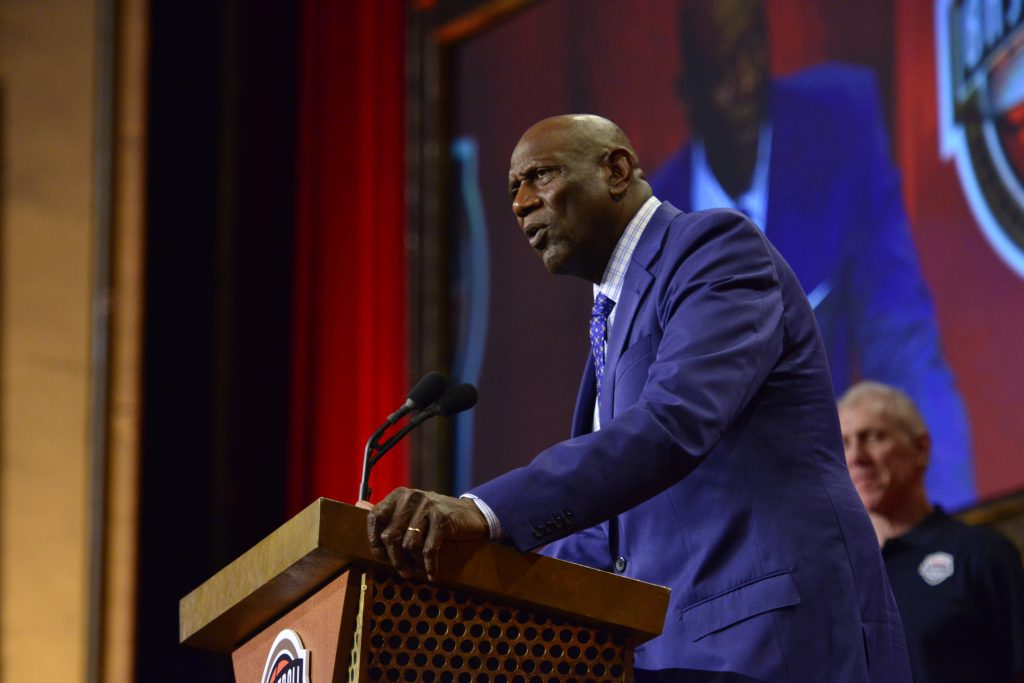

The National Basketball Retired Players Association (NBRPA) is comprised of former professional basketball players from the NBA, ABA, WNBA and Harlem Globetrotters. It is a 501(c) 3 organization with a mission to develop, implement and advocate a wide array of programs to benefit its members, supporters and the community. The NBRPA was founded in 1992 by basketball legends Dave DeBusschere, Dave Bing, Archie Clark, Dave Cowens and Oscar Robertson. The NBRPA works in direct partnerships with the NBA and the National Basketball Players Association. Legends Care is the charitable initiative of the NBRPA that positively impacts youth and communities through basketball. Scott Rochelle is President and CEO, and the NBRPA Board of Directors includes Chairman of the Board Johnny Davis, Vice Chairman Jerome Williams, Treasurer Sam Perkins, Secretary Grant Hill, Thurl Bailey, Caron Butler, Dave Cowens, Shawn Marion, David Naves and Sheryl Swoopes. Learn more at legendsofbasketball.com.

About Girls Inc.:

Girls Inc. inspires all girls to be strong, smart, and bold. Their comprehensive approach to whole girl development equips girls to navigate gender, economic, and social barriers and grow up healthy, educated, and independent. These positive outcomes are achieved through three core elements: people - trained staff and volunteers who build lasting, mentoring relationships; environment - girl-only, physically and emotionally safe, where there is a sisterhood of support, high expectations, and mutual respect; and programming - research-based, hands-on and minds-on, age-appropriate, meeting the needs of today’s girls. Informed by girls and their families, Girls Inc. also advocate for legislation and policies to increase opportunities for all girls. Join Girls Inc. at girlsinc.org.