And the Oscar goes to...

By Peter Vecsey

November 25, 2007 | 10:00am

THE last time I spoke to Wilt Chamberlain, 13 months before he died on Oct. 12, 1999, out of nowhere he appealed: “Don’t ever let people forget how good we were.”

Oscar Robertson was one of those unforgettable, too-good-to-be-true players. While his much-saluted triple-double preeminence makes it impossible for contemporary (i.e. largely oblivious regarding NBA history) fans to overlook, the majority, having only witnessed his meticulous wide-ranging efficiency in grainy film snippets, can’t comprehend such greatness.

What’s more, their captivation with Michael Jordan forbids them from facing the unfathomable reality: There once was a 6-foot-5 guard – the league’s first big playmaker – who was as shrewdly competent and uncompromisingly competitive.

In the minds of many, Jordan’s six championship rings to Oscar’s one abruptly ends all comparisons. The disparity certainly seems to separate the two of a kind. Except for Scottie Pippen, Michael’s crowned Jordanaires were transposable. Oscar didn’t cash in until late in his career when he joined forces with Lew Alcindor/Kareem Abdul-Jabbar.

Conversely, His Airness didn’t have to combat Bill Russell’s Celtics, or Wilt’s 76ers, or Bob Pettit’s Hawks. Meaning the more facts and figures factored into the equation, the more indivisible Jordan and Robertson become.

For example, if you combine Oscar’s first five NBA seasons, he averaged a triple-double. The Elias Sports Bureau has done the math – 30.3 points, 10.4 boards and 10.6 assists. He’s actually one-tenth of a rebound shy of averaging a triple-double for six seasons.

Additionally, “whomever he defended felt like he was bench pressing a California mortgage,” duly notes former Bucks play-by-play connoisseur Eddie Doucette.

This is why numerous antique dealers of league lore – Wayne Embry and Al Attles, to name two – unequivocally identify The Big O as the game’s all-time No. 1 passer and perfectionist as well as its supreme being.

As dumb luck would have it, I caught the full fragrance of Oscar’s majesty at his first recital at the old Madison Square Garden, 50th Street and Eighth Avenue. It was the 1957-58 season and he was a sophomore at the University of Cincinnati, in town to play Seton Hall. I was a high-school sophomore and had been given a ticket to see four college teams that meant nothing to me; the attraction was the stimulation of being at the Garden and the next day bragging to friends about being there.

Man, was that ever the place to be that night. Gushing points like an open hydrant, this guy I’d never heard of before saturated the stat sheet for 56 points. I had no idea a player could be so flawless in so many facets.

“Oscar was an illusionist in sneakers, so smooth and clever on the floor that it was difficult for the average fan to appreciate how accomplished he was,” recalls Doucette, who, just out of college, first saw Robertson with the Cincinnati Royals and later had the opportunity to call the final three seasons of his career in Milwaukee.

“I watched his every move from warm-ups to game’s end and never ceased to be amazed at how anyone 6-5 and 225 pounds could slip, unimpeded, through cracks meant only for shafts of light,” Doucette marvels still.

“There was no flash, no sizzle, no soaring dunks that would elicit ‘oohs’ and ‘ahs.’ Oscar was an economy of effort. You’d never see him work on shots in warm-ups that he wouldn’t use in games. Everything was 18 feet and in. He made his way to the hoop like a safecracker hopscotching a laser grid attempting to get to the vault.”

Attles’ first look at Oscar is indelibly etched in his memory bank. Both were 1960 draftees. Early in their rookie season there was a doubleheader in Syracuse – Celtics vs. Royals and Warriors vs. Nationals. Attles and Philly backcourt partner Guy Rodgers grabbed adjoining seats and focused on the already highly acclaimed Big O.

Almost immediately Oscar did something Attles had never witnessed before. As he came down court on a semi-break, K.C. Jones tried to intercept him, while a trailing Sam Jones tried to head him off at the pass from the opposite side.

Revved up by the recollection, Attles says: “Oscar dribbled by both of ’em. That got K.C. into a heated rush. Oscar quickly stepped in between them and quickly stepped out. Bam! K.C. and Sam banged heads. I’d never seen anything like it.

“I’m not telling you something I heard. I’m telling you something I saw.”

Turning to Rodgers, Attles groaned, “We’re going to have a big problem with this guy.”

Attles’ nickname is The Destroyer. Nobody, no matter how big and bad, wanted a piece of the Newark native. Manhandling opponents (teammates, too, when provoked) was the ticket he punched nightly to ride season upon season.

“But I never rattled Oscar. He never blinked at full-court, hands-on pressure,” Attles says in awe. “And I never blocked his shot. He was never concerned about his defender. He always looked straight ahead at his teammates.”

Robertson’s aplomb for getting teammates involved in the first three quarters played into Attles’ defensive game plan. He knew Oscar would look to score only four to six points in the first quarter, the same in the second and maybe eight to 10 in the third. If the verdict was in doubt in the fourth quarter, he’d go off for 12 to 18.

“If I was lucky, I’d be in foul trouble long before then,” Attles says. There was one time, though, when Attles and Rodgers trapped Oscar near midcourt and stole the ball to preserve a win.

“Listen to me,” Attles says, laughing. “Here I am talking about one incident. Once in my whole career I got the best of Oscar.”

If his grandkids know better, they won’t admit to getting tired hearing that story.

Embry vividly remembers Oscar’s outburst of 56 vs. Seton Hall. It was thoroughly expected. At the time Embry was playing for the Royals. For over a year he’d gained first-hand knowledge of Oscar’s oppression.

“If you were any kind of a player, UC was the place to scrimmage in the offseason or on off days. Typically, winners would stay on the court,” Embry says. “It didn’t take long to realize we needed to get our wins early before Oscar showed up.”

The leading scorer for the Royals when Robertson arrived on the UC campus was Jack Twyman. Shortly afterward, the future Hall of Famer challenged the unflappable freshman to a little one-on-one.

“Jack’ll kill me for giving you this,” Embry cackles, “but he hasn’t won a game yet. Oscar waxed us all.”

Embry and Robertson later became Royals teammates and roomed together. That is when Wayne really found out how driven Oscar was to excel and why he had total command of the game’s rudiments.

Oscar would carry a ball with him wherever he went. In fact, nobody but him was allowed to shoot his ball in pre-game warm-ups or practice, ever, honest.

Embry’s revelations about Oscar are endless. Each afternoon on the road he’d lie on the hotel bed shooting his ball into the air for a couple of hours, a perfect rotation and follow-through every time.

Flushing out every last impurity from his system was a prime objective. So was staying ahead of arch-rival Jerry West. When Oscar wasn’t contending on the court, he was contending off it.

Late one season Embry awoke from his afternoon nap to see Oscar studying the sports pages of the New York Post – in those days the only paper to carry a spread sheet of NBA stats.

“I know what they all think,” Oscar said to Embry. “They all think West is going lead the league in scoring. But I’ve figured out I need to get 48 points against the Knicks to pass him. You had better set me some massive picks tonight, big fella.”

In 1970, Embry became Bucks GM, the league’s first African American to have that position. His initial trade, instigated by owner Wes Pavalon, was for Oscar, who still dominated his position and controlled court proceedings more than the coach. He told Larry Costello what would work and what would be good for the team.

Costello liked Oscar but was uncomfortable with that arrangement.

“I told Coz to let it go,” Embry says. “I told him to let Oscar do what he does best and coach all the other players. I told him to be thankful he can walk into the locker room and see No. 1 in one corner and No. 33 in the other. It should make you feel good you’ve now got a chance to win it all.”

**********

Part 2:

November 30, 2007 | 10:00am

SO FAR, I’ve received 172 e-mails regarding Sunday’s Oscar Robertson column, the biggest reader reaction of 2007 exempting last June’s Bill Russell perspective. January’s name-dropping piece of players and coaches responsible for pushing me into this profession elicited roughly the same response from many people in their 40s, 50s, 60s and 70s.

Clearly, we old folks have incurred little trouble making an Internet transition. My computer definitely helped to coordinate strewn thoughts, prolonging my attention span and enhancing my staying power on one subject.

What’s just as clear is that there are a lot of excitable basketball fans out there, not just the elder generation, mind you, with a craving for the history of the game.

This is precisely why NBA TV initiated a half-hour weekly series, “The Vault” which spotlights – with footage, interviews and studio viewpoints by yours truly, Gail Goodrich and Fred Carter – former players and title teams who may or may not get sufficient credit for their accomplishments.

Robertson and Elgin Baylor were first. The ’79 Sonics were next. This Sunday (6:30 p.m.) the focus is on Mark Price, Andrew Toney and Paul Westphal.

How’s that for a shameless plug? Lucky for you, had I not established a policy early-on in life never to read or a write a book, I’d probably be promoting a novel I just knocked off in this very sentence, or at least take out an advertisement for it on the same page.

But back to the Big O; I can’t put him away without sharing some interesting info that was sent my way off that column.

Thanks to John F. McMullen and Dick Vitale, my consciousness was reawakened to the fact Robertson had outscored Seton Hall, 56-54, the first time I saw him play as a University of Cincinnati sophomore. Numerous other readers swear they attended the doubleheader at the old Garden that momentous evening, too, and I believe ’em all, because each story offered vivid details.

Guess who else was present Jan. 9, 1958? None other than Long Beach High School’s Larry Brown, accompanied by his older brother.

“Cincinnati was recruiting Larry,” e-mailed Herb Brown, currently a Hawks assistant. “Following the game we went to the dressing room. Later we walked to the hotel with the coaching staff and Oscar, who was cradling a basketball. Connie Dierking, from Valley Stream, was the starting center on that team.

“The next day Jimmy Cannon wrote a ‘Nobody Asked Me But’ column about the game. He noted that only about 8,000 people were at the game, but in light of Oscar’s 56 points, every basketball fan in New York City will claim they were at the game.”

Oscar constantly carrying around “his ball,” and allowing nobody to shoot with it, is an enduring image rendered by those who knew him best.

On the first day of training camp of the 1965-66 season, a 12th-round draft choice (No. 88) out of Benedict College, S.C., rebounded Oscar’s ball and shot it.

“Hey, get your own ball, don’t shoot mine,” Oscar scolded Bob McCullough, fresh from scoring 36.5 his senior year, second in the country to Rick Barry.

“Whatcha mean, your ball? Your name Spaulding?”

Robertson and McCullough commenced to exchange harsh words. Wide Wayne Embry was forced to intercede on his teammates’ behalf. He explained to the rising rookie the Royals’ facts of life, but McCullough didn’t want to hear it. This was not the law of his land on the asphalt jungle of New York City, where loose balls and women were up for grabs. He was waived the very next day.

McCullough went back to Harlem and eventually succeeded the deceased Holcolmbe Rucker as tournament commissioner and started Each One, Teach One, a free-of-charge instructive clinic for children.

Each summer in the late ’60s, early ’70s, Embry, who’d become an NBA GM, visited the playground on 155th Street and Eighth Avenue to scout street and ABA talent.

“I’d always make a point of needling Bob,” Embry said, laughing. “I’d tell him, ‘Imagine the pro career you could’ve had if you’d only thrown Oscar his damn ball.’ ”

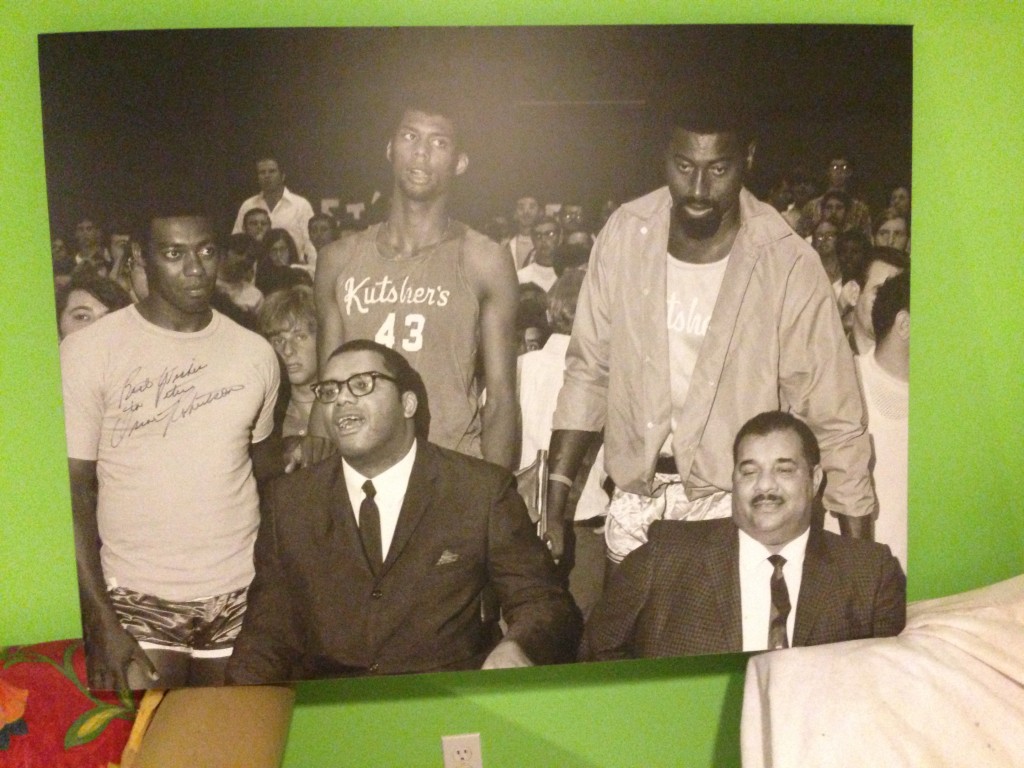

In August 1987, I had the pleasure of experiencing Oscar’s purist spirit directly. I had been invited to suit up for the annual Maurice Stokes benefit, old-timers only (a first for a writer), at Kutscher’s CC.

Oscar and Pete Maravich, 40 and frisky, was the starting backcourt of our squad. Cazzie Russell, Bob Cousy, Bob Davies and Kevin Loughery were on the other side. Midway into the first period coach Dolph Schayes sent me in for Oscar. You should’ve seen his face contort at the blasphemous substitution.

“No (bleeping) way am I going to be replaced by a sportswriter,” Oscar steamed as he stormed back on the court. “No (bleeping) way that’s gonna happen.”

I understood perfectly.

However, had Satch Sanders not gone out on the floor and cajoled Oscar to the sidelines, I would’ve been deprived of the biggest thrill of my sporting life . . . besting the surreal split second in the Rucker (Harlem Professional) Tournament when I delivered a no-look pass on the run to Julius Erving for a bombastic aghast.

Late in the second half at Kutscher’s I found myself on another fantasy fastbreak, a sportswriter and Pistol Pete skipping the night fantastic, with only one man to beat.

Maravich delivered a pass only his kind of showmanship could provide, and he hit me square in the hands in textbook stride with an around-the-back pass; I thank God to this day I was able to convert it into a lefty layup.

“Don’t ever say I didn’t give you anything,” Pistol said.

Five months later, Jan. 5, 1988, while playing pickup ball in Pasadena, Calif., Maravich died of heart failure.