by Sam Smith

Just because things are the way they are doesn’t mean they were destined to be so.

Just because NBA players have the richest guaranteed contracts in American team sports, unlike NFL players, or have so much flexibility in their economic relationships, unlike NHL players, doesn’t also mean it was inevitable. It occurred mostly because a valiant group of determined men, the modern revolutionists of basketball as I refer to them in my new book, Hard Labor, demanded economic equality and social liberty with racial camaraderie during the most turbulent times in American society.

They were the 14 NBA players led by NBA legend Oscar Robertson, along with individual pioneers like Spencer Haywood, Gail Goodrich and Rick Barry and labor titans like Larry Fleisher, who challenged the guardians of the game, the owners of NBA teams and the league itself. These gutsy NBA guys went to court and Congress despite threats to their livelihoods. They did so for their successors knowing none of them would personally benefit from the risks they took to their own careers.

And there were consequences. Robertson lost his job as a national TV commentator for NBA games. Chet Walker felt forced into retirement after averaging 19.2 points his final season. Joe Caldwell was kicked out of basketball under the guise that he had led astray, of all people, Marvin Barnes. Not all suffered or were punished, for sure. But how was it that Oscar Robertson, one of the best minds ever to play the game, never got a coaching, advising or management chance with any team? Coincidence, probably.

Consider those times in the 1960s: NBA players had roommates and washed their own uniforms, local medical people, often veterinarians, were hired to do the pregame taping. There were 20 or more preseason games, two teams traveling together on buses barnstorming through states, playing every night for weeks. And then starting the 80-game season. Airplane travel was, of course, coach, and players would pile into a taxi to get to the game from the hotel. No team bus like today. The team would reimburse the players. Tommy Heinsohn recalls asking for, say, $3.50 and Auerbach saying it cost him $3.25 from the same hotel, so that was all Heinsohn was getting in reimbursement. Philadelphia owner Eddie Gottlieb used to hire a bus to take players to East Coast games, like in New York. He’d sell tickets to fans for the unused seats.

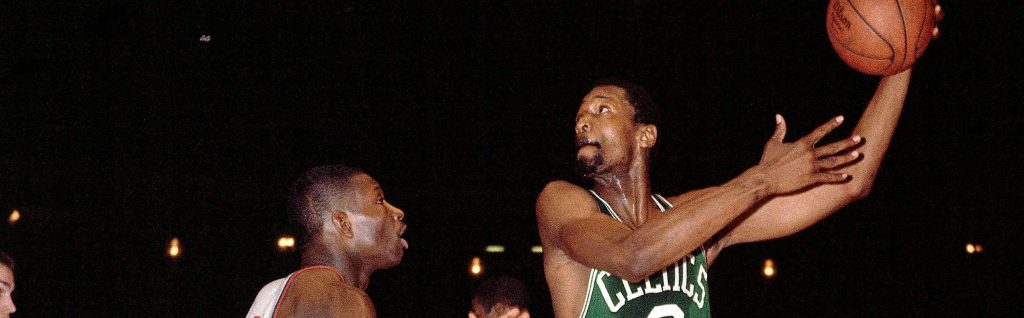

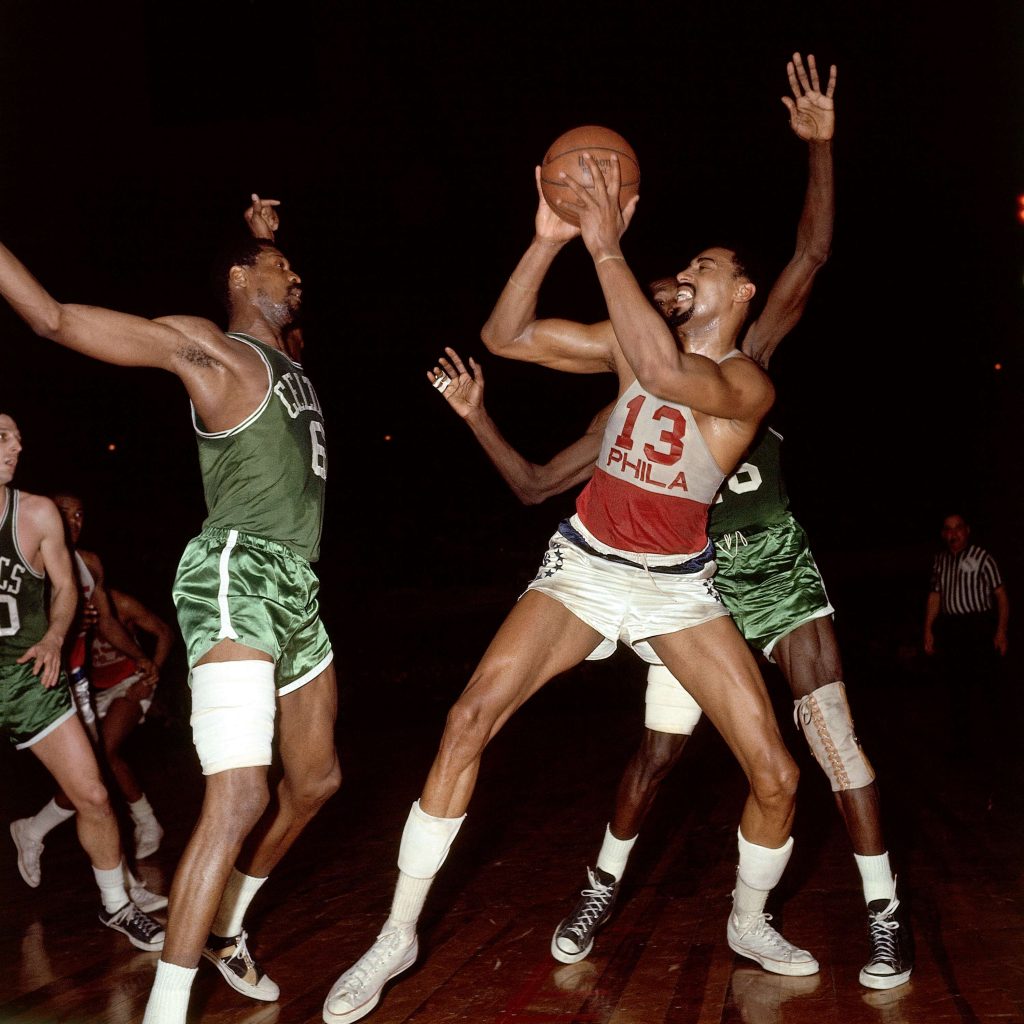

This was also the time of the great migration of black players to the NBA cities, the stars of the game that raised the sport with Elgin Baylor, Bill Russell, Wilt Chamberlain and Oscar Robertson. In effect, the playing field was raised as the NBA became the vertical game the public grew to love.

The 1960s reverberated with the Vietnam War and Civil Rights overshadowing most everything else. Professional athletes contending for their “rights” was hardly a subject of much sympathy. So serious sports magazines published stories of whether the game was being ruined by too many blacks. Anonymous quotes proliferated similar to when Jackie Robinson started with the Brooklyn Dodgers. These brave NBA players also would not back down.

Elgin Baylor once sat out a regular season game when he could not be served at a restaurant with teammates. And this wasn’t the 1940s. This was into the 1960s. Lenny Wilkens was starting for the St. Louis Hawks. His picture was featured with the other starters in the window of a popular restaurant across from the arena. Wilkens was not allowed to eat there with white people. The league would arrange preseason for team hotels to allow blacks, but Celtics players related how the hotel marked “c” in the register to denote “colored” and asked to split roommates because whites and blacks shouldn’t share a room. Also, so the white guests could know on which floors the black guests were staying. This was “sophisticated” Los Angeles. Black players often would use a white teammate as a beard just to get a taxi, the white guy standing outside to flag down the cab and then the black guys rushing out to get in. Yeah, you think a taxi is stopping for us? NBA players? Big deal.

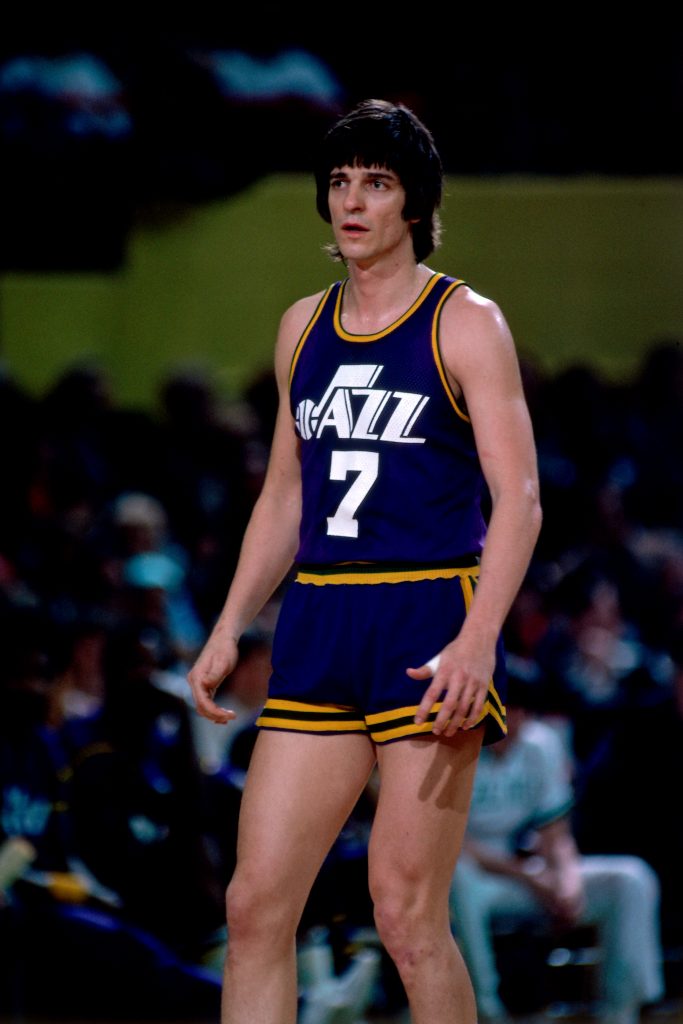

There was a quota system then in which white players replaced white players and blacks replaced blacks, and that teams assigned black players to be rebounders and defenders so the team would not have to pay them as much money. After all, those “role” players scored less. It was the story of the St. Louis/Atlanta Hawks and how the appeal of Pete Maravich to the white South may have short circuited a dynasty. Dunking was at one time even banned in the NBA to level the playing field for white players.

What these players did in the Oscar Robertson suit is mostly lost to the ages, recalled like Yalta, something important, but everyone is a bit fuzzy on the details. But what the Robertson suit did was, effectively, create the modern NBA, allowing for the combination of the rival leagues with the ABA. Effectively marrying the conservative NBA with the liberal ABA, boardroom ethos merging with street ball excellence, inviting the rest of geographical America into the game with small cities from throughout the country. It was surgery that introduced a special sort of doctor, like Julius Erving. But not until NBA players themselves began an evolution to legitimate free agency and the ancillary working benefits, which translated into respect and an eventual partnership that has the NBA flourishing today like no other American sports league. Owners then, of course, screamed ruination of the sport if players could choose where they wanted to play.

Those players dragged the NBA into court and Congress, where none other than Sam Ervin of Watergate fame was astounded by the way the NBA had been doing business so inequitably. Those players led by Robertson challenged the collusion between big business and government that got the NFL a specious antitrust exemption in a back room deal with Louisiana senators in exchange for an NFL franchise, the New Orleans Saints. Long before Curt Flood was making his heroic stand at the cost of his Major League Baseball career, these NBA progressives were demanding equality in the marketplace of ideas as well as finance. Didn’t they deserve the same rights as any working American?

Like the old American Football League, the ABA came along mostly as a ploy to join the NBA. The AFL owners pulled it off with that wink deal in the U.S. Senate. The NBA owners were stanched by the Robertson group that grew from the first players’ association in sports headed by Bob Cousy and then handed off to Heinsohn and then Robertson as the NBA players’ symbol of the equality being demanded in the boardroom and playing field.

They first got the attention of the owners in a unified boycott threat of the 1964 All-Star game, the first scheduled to be nationally televised. The Lakers owner threatened to throw Baylor and Jerry West out of the league. I was able to relate those stories along with the shaky travel of the era when the NBA had its “Sully” moment of the Lakers plane with Baylor on board crash landing in a snowstorm without a scratch to anyone, along with the amazing story of the greatest sports friendship of all time, Jack Twyman and Maurice Stokes, the latter a LeBron James of his era struck down in his prime. The Celtics dynasty would not have been quite so if not for Stokes’ illness.

This was a time when Wilt and Bill Russell continued their rivalry in the summers, traveling around to parks and playgrounds, literally picking sides for games. Earl Monroe almost jumped to the ABA, but when he visited the Indiana Pacers the players all were armed with pistols because they said there was so much KKK activity. Think the game is fancy now. Robertson plaintiff Archie Clark was doing crossovers, and Don Kojis the back door lob dunks in the 1960s. Russell had a famous chase down block in the Finals in the late 1950s.

Equally forgotten or unrealized is this creedal nature of sports, so dismissed with the anti-immigrant tenor of these times. Plaintiff Tom Meschery was from China and was forced to live in a Japanese internment camp during World War II. He might have been considered a chain migration and under attack now. Bob Cousy’s mother brought him to the U.S. when she was pregnant, and he spoke French much of his youth. He might have been under siege as an anchor baby. Heinsohn came from a German family and was mercilessly harassed as a “Nazi” during World War II. The father of plaintiff Bill Bradley’s wife was a Luftwaffe pilot. She became a respected author and university professor educating so many Americans. These immigrants, coming in legally or because their worlds were under siege because that’s what America stood for, became the people we learn from and cheer for.

My book, Hard Labor, wasn’t just about a tug of war for money. It is the rich and detailed story of these pioneer revolutionaries of the game and their amazingly rich era both leveling the economic field they played on and enhancing the stage where we all came to enjoy the greatest athletic performers in the world. My inspiration for the book was the plight of so many of these players from that era, who stepped forward for their peers and the game. None benefited personally from their endeavors. They just believed in fairness and a voice. My hope is the players of today, so wealthy beyond their ancestors imaginations, realize, accept and understand just how they arrived at the place where they are. Those players did step up in the last Collective Bargaining Agreement with extended medical care for all veterans, a big time first step. But there is a greater debt to repay. As the kids yell in the playground when the ball escapes to the other side, “A little help.”