SCOUTING THE NEXT WAVE OF COACHING TALE

by SEAN DEVENEY

Crunching numbers into the morning’s wee hours. Scouring game film until the sun begins to rise. Spending sweaty hours working with the team’s 12th man, trying to smooth out his footwork or his jumper or a new post move.

The bulk of coaching basketball is not about glory. It’s about the sweat and diligence that comes before those few occasional glorious moments, whether it’s on a pro bench or as head coach in a collegiate program. For five rising young coaches, all with the opportunity to move up in the NBA and NCAA, that work has been getting noticed.

JARRON COLLINS

“I LEARNED THE IMPORTANCE OF BEING PROFESSIONAL”

Jarron Collins considers himself lucky. He was among the final players cho-sen in the 2001 draft, 53rd overall, a draft position that seldom yields a fruitful career. Collins never posted impressive numbers (he averaged 3.9 points and 2.9 rebounds), but he stuck around the league for 10 seasons.

That was, in part, because Collins started his career with the Jazz, a franchise that taught him how best to approach his time in the league.

“I was fortunate in that I started by career with John Stockton and Karl Malone, playing for Jerry Sloan,” said Collins, now an assistant with Golden State. “I learned the importance of being professional and doing things in that manner. Because your reputation will go places you will never go. You handle yourself appropriately, take care of your business, it may pay dividends down the road.”

That’s how it went for Collins, who spent the 2009-10 season with the Suns after eight years in Utah. He didn’t play much for Phoenix, logging 7.7 minutes in 34 games, but he left an impression on the team’s general manager at the time—Steve Kerr.

Five years later, when Kerr was named head coach of the Warriors, Kerr brought him on as the team’s player development coach. In his first season on the bench, Golden State won the NBA championship.

Collins was moved from player development to an assistant, but he says titles like that don’t matter much. All coaches on Kerr’s bench share duties.

“On our staff, everybody is responsible for doing scouting and having a voice,” Collins said. “That’s one of the things I appreciate about Steve. He allows all his coaches to have a voice and do presentations and do walk-throughs when it’s your time. It’s like players do reps and get better that way, but coaches get reps, too, and you get better the more repetitions you do.”

That’s important for Collins, who has designs on running his own staff eventually. He interviewed for the Memphis head-coaching job last year and the Atlanta job before that. He did not get either, but he recognizes the value in the experience.

“Interviewing for head-coaching opportunities is always tremendous,” Collins said. “I am definitely very fortunate and appreciative of the opportunities to be in those rooms—it’s only going to benefit me down the road.”

REX KALAMIAN

“THERE’S SO MANY INFLUENCES I’VE BEEN LUCKY TO HAVE”

Rex Kalamian was coaching at tiny East Los Angeles College, where he had recently played as a guard, in 1992 when he got a break, a chance to work in the NBA. There was a downside, though: the job was with the lowly Clippers, notorious penny-pinchers at the time. Kalamian’s assignment was on a game-night basis only, helping out coach Larry Brown and his staff.

Two years later, he was hired to be the team’s video coordinator under coach Bill Fitch, who liked his work ethic so much that he soon made Kalamian an assistant coach.

“I didn’t really know it at the time, how big that opportunity was,” Kalamian said. “It changed my life. Then Bill just became such a big influence in me staying in the league and learning how to coach.”

Things were tumultuous for the Clippers of that era, yet Kalamian remained with the team in some capacity through 2003, working for seven head coaches in that span. He finally left L.A., coaching Denver, Minnesota, Sacramento, Oklahoma City and Toronto over the next decade-and-a-half and working under the likes of George Karl, Scott Brooks and Dwane Casey, forging a reputation for player development work.

“There’s so many influences I’ve been lucky to have,” Kalamian said. “The guys I’ve worked for, they’ve all been Coach of the Year, they all are very accomplished coaches. I would say I’ve probably taken a little bit from each guy.”

Now, Kalamian has come full circle. He’s back with the Clippers, joining Doc Rivers’ staff last year as defensive coordinator. Under owner Steve Ballmer, the franchise has changed drastically in terms of culture and approach. But the biggest change is expectations: The Clippers are among the favorites to go to the NBA Finals. That could eventually lead to a head-coaching job, but that’s not where Kalamian is focused.

“The future is about the Clippers and what happens right now,” he said. “Trying to win a championship. To me that is the focus because teams that win, coaches that win, good things happen to them.”

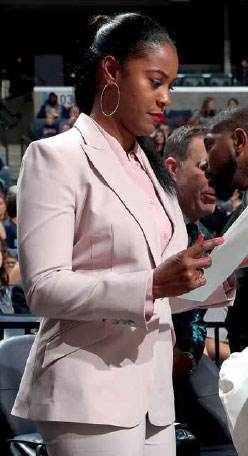

NIELE IVEY

“SHE JUST HAS IT"

Jaden Ivey is one of the top prospects in the Class of 2020, a guard for Indiana’s LaLumiere School. He has committed to Purdue but conceded that when it comes to the family hoops tree, he’s not the top branch. That still belongs to his mom, Niele Ivey—a star and national championship winner as a player, rated as one of the best assistant coaches in the NCAA while spending 12 years on Muffett McGraw’s staff at Notre Dame.

“Yeah, my mom is the one who motivates me,” Jaden said recently. “All the success she has had and where she is now, it’s what I want to do.”

Niele Ivey made the leap last summer from the Fighting Irish bench to Memphis, to join coach Taylor Jenkins’ staff. The Grizzlies have been the biggest surprise team in the league, entering this season expected to finish in the cellar as the franchise undergoes a rebuilding program.

Ivey earned a reputation as a teacher at Notre Dame, both as a coach and in her time as a point guard who averaged 10.8 points and 5.5 assists from 1996 to 2001. Ivey played in the WNBA for five seasons after that.

When Ivey was inducted into Notre Dame’s Ring of Honor in 2016, former play-er Skylar Diggins said of her, “She led by example. If you didn’t know how to do this and that, ‘OK, let me see the ball. Boom-boom-boom-boom-boom-boom—that’s how you do it. She’d get out there and play with us, it was something you can’t really teach. She just has it.”

That hands-on teaching approach made her an ideal fit for the young Grizzlies, who had rookie point guard Ja Morant and star big man Jaren Jackson Jr., both just 20 years old—not much older than her son. This would be a group in need of teaching. That was one reason Ivey had interest in the job.

“Taylor, sitting down and talking with him about his vision, he’s really big on fostering a competitive, unselfish, positive environment for his players,” Ivey told the Memphis Commercial-Appeal. “He’s very development-oriented.”

Turns out the development has happened quicker than expected. Far from the cellar, the Grizzlies are in the mix for a playoff spot in the West and Morant is the favorite for Rookie of the Year. As a fellow point guard, Ivey is playing whatever role she can in that.

“She’s given me some corrections with my game,” Morant said. “Getting to certain spots on the floor. And she’ll tell me I corrected it and she’s proud.”

LINDSAY GOTTLIEB

“I AM REPRESENTING MORE THAN JUST MYSELF”

Of all the glittering elements on her resume, the biggest for coach Lindsay Gottlieb may be this: She’s been to the Final Four. Not as a player or as an assistant. No, Gottlieb got there as a head coach, when she led California to the Final Four for the first time in school history in 2013.

Not many NBA assistants have head-coaching experience in the NCAA and none, other than Gottlieb, have been to a Final Four. That was one reason that John Beilein, himself the former coach at Michigan, wanted Gottlieb on his staff when he took the job as coach of the Cleveland Cavaliers.

“She’s been a winner, her whole career,” Beilein said. “When you go to a place that hasn’t been winning and you change that, that says a lot about a coach.”

Gottlieb became the league’s eighth female assistant coach last spring, leaving her mark as one of the most successful active coaches in the women’s game. She began her head-coaching career at 30 years old, guiding UC-Santa Barbara to a 22-10 record. Three years later, she got the job at California, where the Bears went 32-4 in her second season.

Her Cal teams won 20-plus games and reached the NCAA tournament in seven of eight seasons, and her overall head-coaching record at the end of last year was 179-89.

Gottlieb did not get into basketball to coach. She was recruited by Brown as a guard, but a knee injury limited her ability to contribute on the court. So she began helping her teammates from the bench. Her teammates at Brown nicknamed Gottlieb, ‘Coach,’ and by her senior year, she was a de facto part of Brown’s staff, serving as a player-coach.

Now, Gottlieb is helping to bring along the young Cavaliers. She concedes that there’s pressure attached to her position, but that pressure does not come from Beilein or any of the team’s players. It mostly comes from herself.

“I have seen it as, I am representing more than just myself,” Gottlieb said. “I want there to be more women coaches after me. So the decisions I make and the things I do, I have to look at it that way. It does add pressure. I want to be successful so that more women will get chances to coach at this level.”

BOBBY HURLEY

“THE FIRE WAS THERE TO COACH”

It was the fall of 2000 and Bobby Hurley thought he might have one more comeback. The No. 7 pick in the 1993 draft and one of the most accomplished players in NCAA history, Hurley’s career had been limited after he nearly died in a car crash a few months after his league debut.

He’d had surgery to fix his ACL and was expected to try out for Boston. But the knee was still not right and Hurley, reluctantly, retired at age 29.

It was difficult on him. Hurley tried to shift is focus. He got into thoroughbred racing, owning two horses he raced in New Jersey and Florida.

“I wasn’t able to retire on my own terms, to leave on my own terms,” Hurley said. “That was frustrating. So I needed to get away. It was not like I never watched—I was watching close, college basketball, the NBA. But I needed to have some other life experiences. Doing that gave me the time I needed to work through getting over the finish of my playing career.”

A decade later, Hurley returned to competitive basketball as a coach. He was from a family of coaches, starting with his father, Bob Hurley Sr., who won 26 state championships in 39 years coaching at St. Anthony’s High School in New Jersey. When his brother, Dan Hurley, got the head coaching job at Wagner in 2010, Bobby joined the staff.

“I just had an open mind,” Hurley said. “I was ready for a fresh challenge. I kind of knew deep down that I wanted to coach, that I always wanted to coach, it was such a big part of my life, watching my dad do it and seeing my brother do it. The fire was there to coach.”

From that modest beginning, Hurley has built a budding career. His first head-coaching gig came at the University of Buffalo, where he guided the Bulls to their first-ever NCAA tournament. He left Buffalo after that showing, taking the reins at Arizona State in 2015.

Hurley’s Sun Devils won 20-plus games the past two seasons, getting the school back to the NCAA tournament for the first time since 2014. That’s been especially rewarding considering the way his playing career ended, considering the time off he needed to heal emotionally.

“I just have so much more appreciation for what the game of basketball has done for my life,” Hurley said. “Not having it for those years when I was not coaching or playing, there was a void there. Getting the chance to work with the kids I work with now, it has really replaced that void.”